Across Content Areas

Academically Productive Talk can look different across content areas, but there are also ways APT is particularly valuable that apply to all content areas:

-

Establishing a shared understanding or purpose.

This kind of discussion is often used early in a lesson. It may be used to set up a task in order to make sure all students understand what is being asked of them. For example, before having students engage in a new, challenging task, a teacher might:

- Ask students to discuss the meaning of words used in a text, a problem statement, or a task description in order to ensure that all students have a shared understanding;

- Ask students to talk about the major lessons from prior work that help to set the stage for the current task;

- Ask students to identify differing perspectives in a text before they engage in a discussion or debate supporting one of those positions.

Simply telling students what to do and then moving on may at times be sufficient. But it will be ineffective if some students do not understand the context or purpose. Taking time to listen to students early on may actually save time later by avoiding the need to straighten out misunderstandings or fill in missing understandings when students are stuck. Importantly, if time is not taken to establish a shared understanding, inequities may be exacerbated because students with limited vocabularies or insufficient background knowledge for the task are unable to be successful.

-

Connecting to current thinking or prior experience.

This kind of discourse lays a strong foundation for learning by identifying and engaging students’ current thinking or prior experiences. For example, a teacher might ask:

- Is [this literary character’s] experience like anything you’ve experienced?

- Would you behave differently in this same situation?

- How was life different for these historical figures than it is for us today?

- If we drop these two balls of different weights at the same time, which do you think will hit the ground first?

These connecting conversations are not intended to result in shared understanding; in fact, differences in how students think or in what they have experienced are very productive in raising students' curiosity and interest in the lesson(s) to come.

-

Analyzing a topic or phenomenon.

This kind of discourse is generally at the heart of the learning experience. Students work together to, for example:

- develop a deeper understanding of a scientific phenomenon that is puzzling,

- model a challenging problem situation or consider alternative approaches to solution,

- make and defend arguments about the contributors to historical events, the motives of literary characters, or the relative merits of one solution to a social dilemma over another.

While this type of discussion is time consuming, the outcome it targets cannot be achieved with direct instruction. If the teacher does the analysis, then it is the teacher who has learned to analyze, not the students. Students may be, and often are, asked to read and then independently write an analysis of what they have read. While individual work may serve an important purpose–such as evaluating individual students’ understanding or assigning homework, rather than using class time–it will not achieve the same goal. In discussion, students are pressed to clarify their thinking. Their ideas are extended and challenged by others, stimulating intellectual growth that will not take place when students are working alone.

These discussions thrive on differing ideas or perspectives. At times, the goal is to arrive at a common understanding —such as why a hotpack becomes hot when the divot is turned, or why multiplication and addition arrive at the same answer when calculating volume. And sometimes, the goal is to make and defend legitimately different points of view—such as whether John Brown was crazy for attacking a U.S. arsenal, or whether doctor assisted death should be legal. Unlike connecting discussions, in which each student’s ideas or experiences are equally relevant, these discussions often follow a line of argument, allowing the student whose position is being challenged or who has identified relevant evidence to respond.

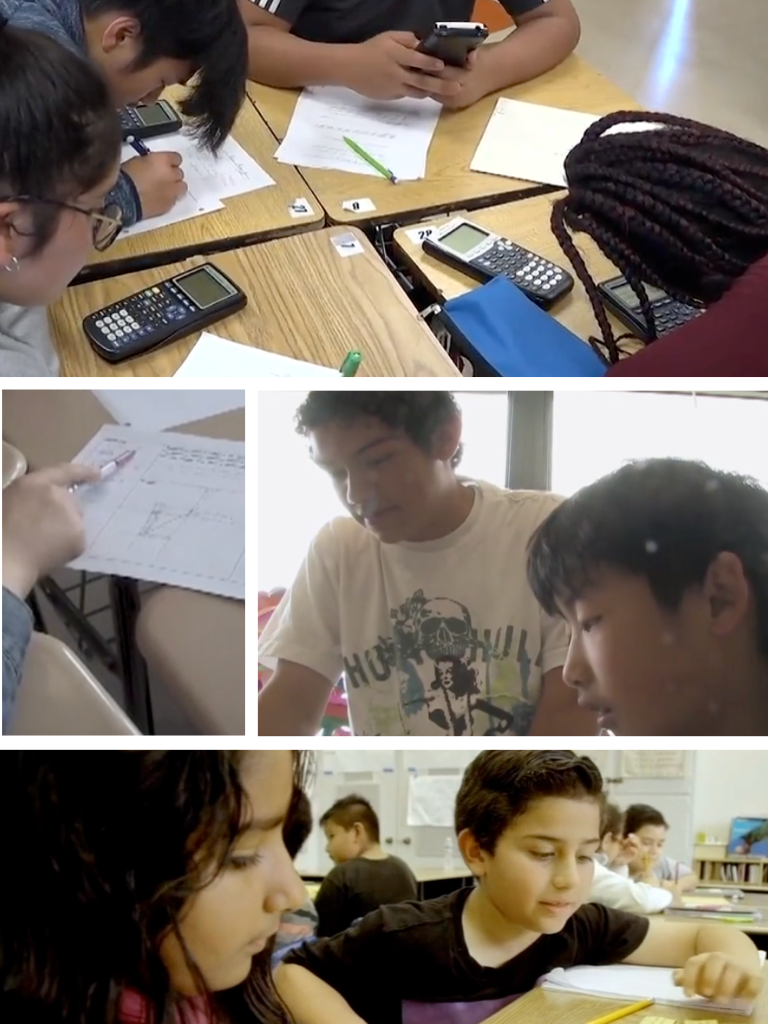

Math

There is plenty to discuss in the math classroom, and discussion can increase students' confidence as mathematical thinkers.

Language Arts

While other content areas use language to learn disciplinary content, ELA classrooms focus on the language itself: on the nature of language and its use as a tool for communication and learning.

Science

Scientific ideas are often counter-intuitive. Common sense leads us to believe that day and night are caused by a moving Sun, that air is weightless, that heavier things fall faster, and that most of the matter in a plant comes from the soil. Science contradicts these beliefs.

Social Studies

The social studies classroom differs from other subject areas because it’s perceived as the training ground for democratic civic participation.